The conflict in Northern Ireland was a turning point for the British army which had to deal with a completely different scenario from the one encountered overseas. According to the words of Corelli Barnett the crisis that the British Army it crossed into Ireland was caused precisely by its purely colonial function, not inclined to measure itself in culturally more similar situations1. It is no coincidence that the use of the army to defeat terrorism was, in this case, a failure that led to a sudden deterioration of relations between Republicans, Loyalists and the British themselves. By force of interposition the soldiers were transformed, in fact, into enemies detested by both the contenders. The only really effective weapon, developed in the post-colonial field and that gave the best results, was the establishment of an information and intelligence apparatus useful to enter the thick meshes set by the members of the IRA so as to reveal the plans and methods of 'action.

The Irish question

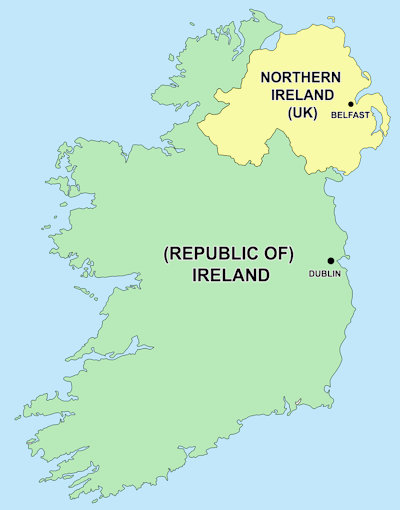

The problems between the United Kingdom and Ireland have a long history behind them that, according to the writer, can not be exhausted in the space of an article. The rebelliousness between Catholics (Republicans) and Protestants (Unionists / Loyalists) arose from a primarily political fact, arising from British rule over a small portion of the Irish island. To this we must add the vexatious attitude that the Protestants adopted towards the Catholic community which, although in the majority, was progressively ousted from any economic, political and social participation2. The rampant unemployment and the economic crisis further aggravated the dissatisfaction of the Republicans who remained exposed, without any defense, to attacks directed by the Loyalist minority. The dialectic clash soon moved on the streets and in the squares where every manifestation of dissent became an opportunity to confront physically. No coincidence that the most serious problem for the management of Stormont was the management of public order because those who had to deal with it did not always demonstrate proper impartiality. In the 1961, for example, the 88% of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was protestant as well as the notorious reserve police, the Ulster Special Constabulary or otherwise said B-Specials, crowded with extremist elements inclined to discrimination3.

In the 1966, during one of the usual rallies, some militants of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) killed two Catholic and a Protestant civilians. It was the beginning of an escalation that persuaded the Republicans to organize themselves independently and on the wave of the Civil Rights Associations born in America, the NICRA was born or Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. The NICRA activists hoped to bring the debate back to the Unionists on a more moderate level, through direct negotiations with the government, but they were only misplaced illusions. The counter-propaganda of Pastor Rev. Ian Paisley inflamed the minds of the Loyalists who took more concrete forms of struggle with often dramatic implications4.

In the 1966, during one of the usual rallies, some militants of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) killed two Catholic and a Protestant civilians. It was the beginning of an escalation that persuaded the Republicans to organize themselves independently and on the wave of the Civil Rights Associations born in America, the NICRA was born or Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. The NICRA activists hoped to bring the debate back to the Unionists on a more moderate level, through direct negotiations with the government, but they were only misplaced illusions. The counter-propaganda of Pastor Rev. Ian Paisley inflamed the minds of the Loyalists who took more concrete forms of struggle with often dramatic implications4.

In the 1969 the Belfast sky turned red when hundreds of Catholic houses were burned. It was one of the saddest episodes in Irish history: in a short time 523 homes were burned and over 5.000 people found themselves without a place to live. On the Republican side, for the first time in years, the IRA, theIrish Republican Army, the only one capable of defending - even with arms - the rights of Catholics. Despite the hopes placed on the organization, the offensive force of the IRA was really ridiculous: the weapons were few and outdated, while the poor and poorly organized militants. Given the situation, the board of the IRA tried to assert its rights to the Unionists by associating with the civil rights representatives in order to remove political confrontation from the streets. From that moment the IRA was accused of cowardice and many of them misrepresented the meaning in IRA "I Ran Away ". So in December 1969 the Republican organization split into two factions giving life to the PIRA or Provisional IRA (or even Provos heirs of the famous Belfast Brigade of the 1920s) in opposition to the weaker action of the OIRA Official ANGER. In this regard it is correct to remember that both the Catholic fringes were dedicated to the armed struggle, animated by the same desire to pre-order attacks against both the Unionists and the political party Sinn Féin.

The English intervention: operation Banner

The British government, presided over by then Prime Minister Harold Wilson, looked with grave concern at what was happening in Northern Ireland, but Parliament was unanimous about the willingness not to get involved in what looked like a "trap" without Exit. Downing Street confided that the RUC was somehow able to contain the wave of violence, but after the burning summer of the 1969 the death toll began to get serious and a wait-and-see attitude could become very dangerous. Between July and August, 10 people and 899 wounds were killed, including 368 RUC agents. In light of the facts, the 14 August 1969, the British government opted for a "measured" military intervention officially giving way to the operation Banner with the deployment of the army in support of public order activities. The then Minister of Defense, James Callaghan, immediately mobilized the 39th Airportable Brigade stationed in Lisburn, not far from Belfast. Initially the main difficulty of the English soldiers was to assume equidistant behavior between Republicans and Loyalists and to defend both of the one side and the other faction.

During the summer of the 1970, the PIRA intensified its sabotage activities by leading the public demonstrations to generate real city battles. The British military, in anti-riot gear, were appropriately provoked to trigger exaggerated reactions which only increased the resentment of those who were now perceived as occupiers. The strategy of the IRA aimed to erode the credibility of the army in the eyes of the population and the bloody episodes of the Bloody Sunday (30 January 1972) in Londonderry definitively canceled the intentions of peacekeeping of the British military5.

During the summer of the 1970, the PIRA intensified its sabotage activities by leading the public demonstrations to generate real city battles. The British military, in anti-riot gear, were appropriately provoked to trigger exaggerated reactions which only increased the resentment of those who were now perceived as occupiers. The strategy of the IRA aimed to erode the credibility of the army in the eyes of the population and the bloody episodes of the Bloody Sunday (30 January 1972) in Londonderry definitively canceled the intentions of peacekeeping of the British military5.

The first British soldier to lose his life during i Unrest was the twenty year old Robert Curtis, artilleryman of the Royal Artillery, assassinated the 6 February 1971 in the New Lodge area in Belfast. At the end of the year the British soldiers killed went up to 45 and the following year - considered the most bloody - was reached the peak of fallen 129. Also in the 1971, the British government registered 2.404 bomb attacks and 12.387 incidents caused by firearms in a country of just one and a half million inhabitants6. The scenario was really disturbing because the IRA - whose offensive capabilities had improved thanks to arms and funding from generous American benefactors - had gained control of entire urban areas, not to mention in the counties where the terrorists found safe logistical bases .

The convulsive situation and the impotence in the face of the spread of unrest, led the British government to adopt exceptional measures such as Operation Demetrius and the introduction of arbitrary arrest, without trial, for terrorism suspects. Beyond international protests for a gross violation of human rights, Demetrius led to the arrest of more than 400 suspects, but above all began to flow vital information on the way I act of the IRA7.

THEIrish Republican Army

At the end of the 1969 the leaders of the PIRA signed a declaration of intent very important because it placed the Republican paramilitary organization in a different context, at least in substance, by the most famous Marxist terrorist organizations. The Irish army was born, in fact, as a body of protection for the Catholic community which was not able to respond to the injuries of the Protestants8. The IRA was thus able to mobilize Catholics en masse, establishing itself as the only force capable of defending and directing its militants as a real national army. In essence, the IRA managed to channel the interests of Roman Catholic conservatives who were proponents of true nationalism and Marxist revolutionaries whose goal was uniquely united Ireland, the end of discrimination and the cessation of all English influence9.

The dense defensive network designed to protect its members made the IRA an impenetrable organization; the availability of the population - more or less voluntary - constituted an essential part of the operative gear which, from the 1970, had been fragmented into several independent cells for appropriate security needs (Active Service Unit ASU) - at least externally disconnected from the command center. The daily operations were coordinated by a Army Council chaired by seven people including a commander of staff, a general aide and even a quartermaster. The supreme direction was instead to the General Army Convention whose meetings, by statute, took place only every two years; the same organism selected the 12 members for theArmy Executive who used to meet every 6 month. The passage of information and the coordination between the different sections was the prerogative of the General Headquarters Staff which served as a link between the North and the South, a subdivision consistent with the geographic arrangement of the counties. The militarized structure of IRA was very effective, but this type of hierarchical organization chart seemed permeable to the threat of infiltrators or so-called "Freds", The traitors who decided to pass news to the British authorities.

Of all the offensive tools employed by the IRA, improvised explosive devices and mortars were among the most fearsome: thanks to the work of the Irish bombers, generations of terrorists learned to make bombs of all shapes, using components easily found on the market. The most used exploding material was the Semtex coming from Libya, together with the large quantities of fertilizer (ammonium nitrate) usually used to fertilize the land. For the RUC and the English it was of fundamental importance to learn the method by which weapons, materials and people were moved, but it was necessary above all to understand in advance what the targets of the bomb attacks would be that, more than anything else, sowed the terror among the people. For this reason it was important to set up a surveillance service on the streets, which was not limited to the conspicuous patrols of soldiers. In fact, it was necessary to act with discretion, to insinuate itself among the population and to carefully report every suspicious movement in the neighborhoods and in the Northern Ireland countryside.

La Mobile Reconnaissance Force

The urban patrol of the British army carried out a routine vigilance even if, with experience, the command preferred to displace the same departments, for several shifts, in the same area in order to familiarize them with the difficult popular neighborhoods of the Irish cities. Outside the city network the problems were the same, only the threat of ambushes was even more unpredictable.

Apart from that, they used specialized units for the clandestine war with infiltrated agents and teams prepared for long and risky undercover observation shifts. The IRA had eyes and ears everywhere and any unusual presence was promptly reported to those in duty: going unnoticed was actually the hardest thing.

In the seventies the British command in Northern Ireland created the first surveillance units, the MRFs or Mobile Reconnaissance Force strongly wanted by Brigadier General Frank Kitson, commander of the 39a Brigade in Belfast10. Kitson, a veteran of the campaigns in Kenya against the Mau Mau and in Malaysia, reiterated the methods of the counterinsurgency, including psychological warfare with the establishment of one Information Policy Unit who would take care of the propaganda11.

Former Simon Cursey remembers that to get into the MRFs it was necessary to be prepared soldiers, having at least three years' worth of service and a good military record with two or three service shifts in Northern Ireland. Each element of the MRFs had to be accustomed to the use of any weapon, including the "white" ones, having first aid rudiments and familiarity with the communication tools12.

In the MRFs, they had access to boys of Irish descent, easily exchangeable for the premises, who were often supported by the Freds. At the beginning - as Cursey recalls - the observation teams' operations were essentially based on non-commissioned officers, while the officers remained on the "upper floors" as planning officers. In the common imaginary, the Irish neighborhoods appeared like a long row of houses all connected to each other with small courtyards and staircases: main streets from which narrower narrow streets led out who knows where. This was the environment in which the MRF fought their war, walking among the people and interloquing with the inhabitants of the neighborhoods. The enemy had no uniform and anyone could see their presence and report it to some IRA militants. The services of the MRF were so confidential that they were unknown even by the General Staff, but it happened that Sergeant Clive Williams was sent to the Martial Court for shooting, apparently without reason, against a group of men stationed at a bus stop in Belfast. Williams' defensive note then revealed that the suspects were armed and were so acquitted; nevertheless during the interrogations it unveiled important details about the clandestine war fought by the MRF. Undercover work could lead to irreparable errors, such as the involuntary assassin of brothers John and Gerard Conway, mistaken for two IRA militants who escaped from Maidstone prison. For this reason the MRF, modeled on patrols counter-gangs established by the British in Kenya and Palestine, they were judged to be unreliable because their actions were based on too haphazard intelligence work13. One of the most significant episodes in the history of the MRF was that of the Four Square Laudry, that is to say a false laundry in which data and information on potential belonging to the IRA were collected. All the clothes arriving in the shop were secretly sent to the headquarters of Lisburn where experts who provided explosives examined them to detect any traces of explosives. Once analyzed the clothes were taken to a real laundry for the cleaning service and then returned to the Four Square to be returned to their rightful owners. Some members of the IRA had noted that the service van was often parked in the Lisburn Road area, but they also knew that the owl van system had already been used in Israel by the killer squads14. The whole operation was unveiled thanks to the double-entry of a Fred which allowed the IRA militants to eliminate the surveillance team (a man and a woman who survived) who were traveling on the van.

In the MRFs, they had access to boys of Irish descent, easily exchangeable for the premises, who were often supported by the Freds. At the beginning - as Cursey recalls - the observation teams' operations were essentially based on non-commissioned officers, while the officers remained on the "upper floors" as planning officers. In the common imaginary, the Irish neighborhoods appeared like a long row of houses all connected to each other with small courtyards and staircases: main streets from which narrower narrow streets led out who knows where. This was the environment in which the MRF fought their war, walking among the people and interloquing with the inhabitants of the neighborhoods. The enemy had no uniform and anyone could see their presence and report it to some IRA militants. The services of the MRF were so confidential that they were unknown even by the General Staff, but it happened that Sergeant Clive Williams was sent to the Martial Court for shooting, apparently without reason, against a group of men stationed at a bus stop in Belfast. Williams' defensive note then revealed that the suspects were armed and were so acquitted; nevertheless during the interrogations it unveiled important details about the clandestine war fought by the MRF. Undercover work could lead to irreparable errors, such as the involuntary assassin of brothers John and Gerard Conway, mistaken for two IRA militants who escaped from Maidstone prison. For this reason the MRF, modeled on patrols counter-gangs established by the British in Kenya and Palestine, they were judged to be unreliable because their actions were based on too haphazard intelligence work13. One of the most significant episodes in the history of the MRF was that of the Four Square Laudry, that is to say a false laundry in which data and information on potential belonging to the IRA were collected. All the clothes arriving in the shop were secretly sent to the headquarters of Lisburn where experts who provided explosives examined them to detect any traces of explosives. Once analyzed the clothes were taken to a real laundry for the cleaning service and then returned to the Four Square to be returned to their rightful owners. Some members of the IRA had noted that the service van was often parked in the Lisburn Road area, but they also knew that the owl van system had already been used in Israel by the killer squads14. The whole operation was unveiled thanks to the double-entry of a Fred which allowed the IRA militants to eliminate the surveillance team (a man and a woman who survived) who were traveling on the van.

The special observation units were dissolved in the 1973 to be supplanted by the best trained 14th Intelligence Security Company otherwise known as "The Det".

La 14th Intelligence Company

The MRFs did not disappear from circulation, although a large part of the surveillance work was entrusted to a new team of just 50 men, some of whom had trained in Hereford, at the SAS15. Only some 14sima agents were already 22 °, but the company mainly recruited from the army and the Royal Marines. In the 1975 the The it was structured on more solid bases with small detachments of about twenty elements commanded by a captain. To mislead information captured by terrorists, the intelligence unit assumed different names; for example the men recruited for the detachment were unofficially incorporated into the NITAT (INT) o Northern Ireland Training Advisory Team (Intelligence)16. The type missions of the The Det consisted mainly in setting up observation posts (OP's - Observation Posts), the tracking and mobile surveillance of suspects with owl cars, otherwise known as "Q cars ". The stalemates were carried out by groups of two or four soldiers who acted connected with other OP's and counted on the immediate support of a QRF or Quick Reaction Force army or police. In case of necessity the intervention of the QRF could prove to be dangerous, above all if there was an ongoing conflict in fire: it happened, in fact, several times that the army and the police did not know which side were the "friends", dressed in same way of the "enemies"17.

Each observer was armed with short weapons and H&K Mp-5K machine guns, also used by the 22nd regiment. The most important thing, as for the MRF, was to mix the infiltrated agents with the surrounding environment: each operator had to forget his more martial attitudes, giving an image of himself more unkempt, with long hair and - if he preferred - getting grow a Mexican mustache, according to the SAS preferred style. Camouflages were replaced by jeans, pullovers and crude jackets similar to those worn by the working class of Belfast and Derry18.

Obviously the human eye was supported by the use of advanced technological systems with night cameras, infrared detectors, ultra sensitive microphones, hidden cameras of all sizes and sophisticated radio interception systems19.

Il The provided a model for other types of units that performed similar observation and interception services. In the 1977 Major General Dick Trant introduced the Close Observation Platoon (COP) based in the county of South Armagh, the IRA's main county. The COP - as Mark Urban explains - did not overlap with the work of the 14 company, but rather procured primary information on a particular area to facilitate the subsequent work of the specialists. The RUC also provided itself with a special anti-terrorist company, the Special Patrol Group within which the Bronze Section subsequently became the E4A Unit used mainly in urban areas, while the The Det it was deployed in rural areas.

Il The provided a model for other types of units that performed similar observation and interception services. In the 1977 Major General Dick Trant introduced the Close Observation Platoon (COP) based in the county of South Armagh, the IRA's main county. The COP - as Mark Urban explains - did not overlap with the work of the 14 company, but rather procured primary information on a particular area to facilitate the subsequent work of the specialists. The RUC also provided itself with a special anti-terrorist company, the Special Patrol Group within which the Bronze Section subsequently became the E4A Unit used mainly in urban areas, while the The Det it was deployed in rural areas.

From the beginning the IRA terrorists, when they ran into some ambush ordered by the 14 Intelligence Company, they believed the authors were from the SAS and this was true for any unofficial operation conducted by the British army. Among the Republican militants a sort of paranoia crept into the presence of the 22 ° which caused several innocent victims. In the 1974 a helpless 18-year-old Pakistani hired in a military bar was shot dead in the back of the head by some terrorists who suspected he was a SAS operator. The same happened in July when a 21-year-old truck driver was tortured and executed by the IRA in the western part of Belfast: he too was accused of being an infiltrator of the SAS while he was just a military man on leave20. Of course the The Det learned techniques and tactical procedures from the 22 °, as well as to boast in its ranks different operators of Hereford, but the official arrival of the British special forces was subsequent to many of its operations.

1 A. Edwards, Northern Ireland's "Troubles", 1969-98: Principles versus Practice in Counterinsurgency, in A History of Counterinsurgency, vol. II, Santa Barbara, California-Denver, Colorado, 2015, p. 259.

2 Ireland was freed from British rule in the 1947, while Northern Ireland remained in England, run by a Protestant parliament with an administrative seat in Belfast in Stormont Castle. The newly formed Irish Republic did not accept this state of affairs and began to press for Northern Irish Catholics to oppose the union in London.

3 M. Ranstrop-H. Brun, Terrorism Learning and Innovation: Lessons from PIRA in Northern Ireland, CATS Center for Asymmetric Threat Studies, 2013, p. 7.

4 Northern Ireland's "Troubles", op. cit., p. 257.

5 In the 1972 the English Parliament decided to dissolve the Stormont Castle government and replace it with the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland so as to direct the Irish issues directly from London.

6 K. Wharton, At Long War. Voices from the British Army in Northern Ireland 1969-1998, London, 2010, p. xxxvi.

7 Operation Banner. An Analysis of Military Operations in Northern Ireland, British Army, Prepared under the direction of the Chief of Staff, July 2006, URL: https://www.vilaweb.cat/media/attach/vwedts/docs/op_banner_analysis_rele...

8 Terrorism Learning, op. cit., p. 13.

9 Northern Ireland's "Troubles", op. cit., p. 260.

10 M. Urban, Big Boy's Rules. The SAS and the Secret Struggle against the IRA, London-Boston, 1992, p. 35.

11 M. Urwin, Counter-Gangs. A History of Undercover Military Units in Northern Ireland 1971-1976, Glascow, 2012, p. 6.

12 S. Cursey, MRF Shadow Troop, London, 2013, p. 52.

13 J. Moran, From Northern Ireland to Afghanistan. British Military Intelligence Operations, Ethics and Human Rights, London-New York 2013, p. 38.

14 Counter-gangs, op. cit., p. 19.

15 J. Adams-R. Morgan-A. Bambridge, Ambush. The war between the SAS and the IRA, London, 1988, p. 72.

16 The tasks of NITAT were actually to prepare the soldiers destined in Northern Ireland who were stationed in England, but also in Germany. In the 1978 the British headquarters suspected that the NITAT hid some unclear activity and for security reasons the employees of the 14 company became Intelligence and Security Group (In or Sy Group). In the 1980s, the new 14 was coined Intelligence and Security Company. M. Urban, cit., P. 39.

17 The first agent of the 14 Intelligence Company to fall victim to the fire of the IRA was the captain Anthony Pollen of the Coldstream Guard, killed because he was discovered while he was photographing a parade in the Bogside, a Catholic stronghold in Londonderry.

18 J. Rennie, The Operators. On the Streets with 14 Company, London, 1996, p. 85.

19 BA Jackson, Counterinsurgency Intelligence in a "Long War". The British Experience in Norther Ireland, in Military Review - Rand Corporation, Janauary-February 2007, p. 80. URL: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reprints/2007/RAND_RP1247.pdf

20 Ambush, op. cit., p. 74

(photo: web)