The dawn of 2 July 1993 still had nothing to tell, it was a day like many others in the troubled Somali land. The sunset of that July 2nd, however, screamed pain, dismay and fear.

After 23 years from the events of the Pasta Check-point, Somalia is still one of those countries where you don't live but survive.

A country that evolves, is updated but is still extraordinarily linked to a past made of bad habits and false hopes.

Instead of being led by the warlords today, Somalia is worn down by Islamic terrorism, which has built up immense power over those old domestic diatribes.

Today, as twenty years ago, Italians are at the side of the Somalis, witnessing how violence can not undermine the desire for change.

Just before the sun appeared on the horizon, the Italian soldiers in the IBIS international mission were ready for a new day.

Operation "Canguro 11" began around 4 in the morning, the Italian forces divided into two mechanized columns (Alfa and Bravo) had the task of carrying out a roundup aimed at cleaning up the Uahara Ade neighborhood. Area known as the “Pasta” Check-point.

The purpose of this operation was to seize arms and ammunition to subjects who continued to use violence as a means of obtaining what they thought was rightfully theirs.

The use of weapons - in the context of civil war - prevented the proper carrying out of the work of our soldiers and NGOs. The containers full of humanitarian aid, medicine and clothes were attacked, replenishing the ranks of an immense and profitable black market.

Corso XXI Ottobre and the Imperial Road leading to Balad, two fundamental communication arteries for the town, converged around the Check-point.

The two groupings Alfa and Bravo had the task of isolating the left and right side of the area where the operation took place. The Incursori of the ninth Col Moschin, supported by the Carabinieri of Tuscania and the para of the 5th company of the 183 ° Nembo, had to complete the raking.

In reserve there were eight M-60 heavy tanks of the Ariete brigade and some Centauro blinds.

For the third dimension, Ab 205 helicopters were used, crossing the sky together with the assaulting Mangusta A-129. On board the machines the officers had the task - in case of necessity - to coordinate the actions of fire and signal the dangers for the men on the ground.

Although with a decidedly smaller deployment of forces, operations such as the 2 July were almost daily. Kangaroo 11 was not supposed to be different.

Considering that the neighborhood between "Pasta" and "Ferro" was strongly influenced by the presence of General Aidid's men, the Italian one was not just a mopping up operation. The national command had deliberately deployed a number of forces greater than the norm to focus precisely on the dissuasive effect, there was what was called a "show the force".

On other occasions, showing how much the Italian contingent and that of other countries were impressive had reduced attacks on soldiers and had significantly improved relations with the population.

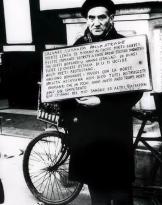

General Bruno Loi was a far-sighted commander in many ways. With extraordinary military strategic ability he held a role of commander that had never before been held by anyone. Every aspect of his operations was calculated so that from each one would derive the maximum strategic advantage, the attention to the behavior of his men and their attitude towards the population made the Italian contingent the most respected of all.

The roundup unearthed several weapons depots and some Somalis were arrested for questioning. The procedures were followed to the letter, no one until then had needed to fire a single shot from his weapon, no one thought that "Pasta" would soon become their first time.

The first riots began around the 07: 30 AM in the area of the "Alfa" group that was falling back on the "Ferro" Check-point. The air was rendered unbearable by the burnt tires, barricades were hoisted almost from nothing around the Italian soldiers.

No one reacted, they were all astonished but thought that everything like the other times would have gone the right way.

When the contingent heard the first shot of a weapon it seemed all unreal. It was a shock, but with the first splinters of grenade the Italians had understood that Somalia began to ask for its blood tribute.

As per Somali military tradition, women and children lined up before our half-sized women. They railed, spat, insulted not in Somali, but in Italian. Not too timidly, the first Ak-47s and RPGs appeared. Immediately afterwards the snipers begin their systematic work against the Italians.

After the initial shock, now it was necessary to respond to the fire avoiding the innocent.

For the “Bravo” group the situation was certainly no better. The second lieutenant of the Lancers of Montebello, Andrea Millevoi leaned out from the turret of his Centaur to follow the evolution of the situation; a bullet hit him in the head, killing him instantly.

Given the evolution of the situation, the first M60 tanks were brought together; however the tankers were not allowed to use their heavy weapons.

Three Vccs continued close to each other, when they were hit by a ferocious fire of automatic weapons. The first crawler is able to return fire with the weapons on board. For the second armored vehicle the fate is different. The militiamen equipped with an RPG-7 rocket launcher fire on the vehicle, regardless of the lives that move inside it.

On the middle, among others, Pasquale Baccaro, par of the 187 °, was shot to death by the fiery dart while operating his on-board weapon.

Inside the VCC is hell: the sergeant major Giampiero Monti has a torn abdomen, the parachutist Massimiliano Zaniolo the devastated hand. The men of the rest of the column line up radially to defend the wounded and allow time for help to arrive. Lieutenant Gianfranco Paglia coordinates the action, while the more advanced Vcc, in the open, covers the soldiers on the ground at the center of the crossroads.

The nightmare of every soldier is to become prey to his enemy, it seems that in Somalia the nightmares come true.

Ambulances and rescue services are blocked by the intense enemy fire and the barricades. The entire district is in revolt.

Ignoring the rules of engagement one of the chief wagons answered a series of wild shots with eight 105 mm shots.

Nobody wanted to shoot, but at stake there were human lives that nothing had done except to believe in a Somalia that they no longer even believed the Somalis.

The Italian command, after recovering from the dismay of the ambush, orders a counterattack that is led by the "specialists" of Col Moschin and Tuscania.

The Somalian reaction is unexpectedly violent. A tough house-to-house battle will develop, during the assault the sergeant major of the raiders Stefano Paolicchi was shot to death.

At the end of the "Pasta" action remains in the hands of the Somalis.

The Italian command, remaining faithful to its values, does not use heavy weapons on the civilian population that acts as a shield to real guerrillas. You withdraw.

A good job of leadership can be seen from how much one is willing to lose in the immediate future to conquer more in the future.

At the Pasta Check-point we risked losing not only other men, but also the honor that had accompanied us during those four months of the mission.

That 2 July there were not only professional soldiers, such as the Carabinieri Paratroopers of Tuscania or the Paratroopers of the ninth "Col Moschin", there were also many conscripts, such as the Paratroopers of the 186th Regiment and those of the XNUMXth Lancers Regiment of Montebello. All of them, professionals and non-professionals, reacted with composure, mastered fear, acted as soldiers in the highest sense of the term.

They would have liked all of them to repay blood with their blood but as soldiers and Italians, they showed how the good of the mission comes first and then everything else.

The Check-point was taken over by the Italians a few weeks after the tragedy, General Loi had once again used his head and then the weapons.

The Italians left in the field, in addition to the three fallen, 22 injured, some of them very serious.

The noise of the C-130 that brought home the bodies of our compatriots silenced the controversy for only a few moments, but it did not matter. That day shocked the lives of many people, changed the story and wrote it at the same time.

The sunset of 2 July 1993 leaves no doubt that the dawn in Somalia can be terribly deceptive.

Denise Serangelo

Andrea Millevoi, second lieutenant of the Lancers Regiment of Montebello, Gold Medal for Military Valor (MOVM) in memory; Stefano Paolicchi, sergeant major of the 9th "Col Moschin" Parachute Assault Regiment, Gold Medal for Military Valor (MOVM) to memory; Pasquale Baccaro conscript corporal at the 186th Parachute Regiment "Folgore", Gold Medal for Military Valor (MOVM) to memory.

The attack leaves paralyzed the then lieutenant Gianfranco Paglia, a paratrooper, who during the action was hit by three bullets while trying to rescue the crew under enemy fire. He was awarded the gold medal for military valor.

Senior military paratrooper Francesco Trivani is also awarded the gold medal for military valor; the corporal Ottavio Bratta and the sergeant Incursore Giancarlo Cataldo Tricasi, later decorated in 1995 with the honorific order of merit of the Italian Republic.